These interaction patterns dictate how reliably a line maintains its target rate. When they compound, production teams face more variability, more interventions, and shorter periods of true steady-state performance.

For decision makers responsible for output, OEE, and return on capital, these system dynamics introduce uncertainty into planning and weaken the financial case behind the investment. Throughput becomes less predictable. Ramp-up takes longer. The line demands more labor attention than modeled. The issue is not with individual machines but with the system as a whole, and that system must be engineered to run as one.

The Limits of a Machine-First Model

OEMs play a critical role in packaging automation projects. Their equipment is proven, their engineering depth is significant, and their platforms reliably perform essential functions. The limitation is not with their machines but with the natural boundaries of a machine-first approach. When recommendations are shaped around a single equipment platform, the customer’s options narrow and the path to system-level performance becomes constrained.

These limitations rarely appear on their own. They emerge from normal operating variability that compounds across interconnected machine centers.

As production environments demand more flexibility, higher speeds, and broader SKU mixes, several structural limitations emerge in Machine-First Models:

1. Recommendations shaped by a proprietary ecosystem

OEMs understandably optimize solutions around their equipment families. This can limit the ability to choose the best machine for each position on the line when another supplier may offer advantages for a specific function.

2. Limited visibility across system alternatives

OEMs have deep expertise in their machine-center technologies but are not positioned to evaluate the full spectrum of market options or the system-wide implications of mixing multiple platforms.

3. System architecture shaped by platform constraints

Lead times, machine configurations, and platform limitations often force design decisions that prioritize equipment availability over operational strategy. This narrows design flexibility and reduces the ability to optimize flow, accumulation, and system performance across the full lifecycle.

4. Systems designed around current needs rather than future growth

Many providers design packaging systems to meet today’s immediate requirements without engineering for rate increases, SKU expansion, or operational evolution. This short-term view limits scalability and forces costly redesigns as production needs change.

5. Lack of Unified Ownership Across the System Lifecycle

When no single provider is responsible for engineering and aligning the full system, equipment interactions, controls logic, and conveyor design are coordinated independently. Each contributor delivers its portion, but no champion owns how the line must behave as a whole. This fragmentation often carries into operation: OEMs support their individual machines, but long-term line performance depends on consistent behavior across technologies, controls, and operators. No OEM is structured to own the lifecycle of a multi-platform system, leaving no unified owner for system-level outcomes.

These constraints are not shortcomings of OEMs as much as they reflect the structure of an approach designed around machines, not systems. As packaging lines become faster, more flexible, and more interdependent, the limits of a Machine-First Model become evident, and the need for an OEM-neutral, system-level perspective increases.

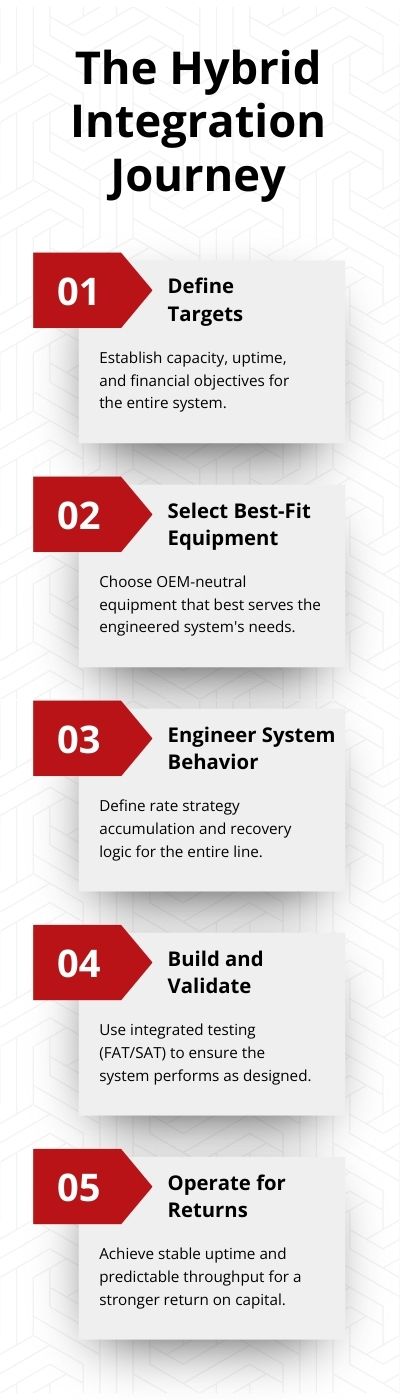

The Hybrid Integration Model: Engineering-Driven System Performance

The Hybrid Integration Model takes a systems-first approach to the design, specification, and delivery of packaging lines across the full project lifecycle. Engineering defines the system architecture before equipment is chosen, ensuring that each machine center supports the full line’s operational requirements.This aligns equipment, engineering, controls, and support around a single objective: stable, efficient system performance that maximizes uptime.

OEM-neutral equipment selection and specification define this model. Each machine center is selected for the role it must play in the system, not for how it fits within the boundaries of a single platform. By prioritizing system requirements over equipment availability, based on current and future goals, this model protects engineering flexibility and ensures the final configuration reflects what the operation needs to run consistently and efficiently.

Hybrid Integration delivers its value by leveraging both technology and service. Technology defines how the system should run through engineering, controls, and line architecture. Service brings that design to life through installation, commissioning, training, and lifecycle support. One without the other cannot produce the system-level performance a modern operation requires.

This systems-first discipline continues through all stages of packaging line engineering. Line architecture, rate behavior, accumulation strategy, recovery logic, and operability are defined through a unified engineering lens. Interactions and dependencies are resolved before procurement, preventing the mismatches that may appear in machine-first projects under real production conditions.

The Hybrid Integration Model represents a fundamentally different way of designing packaging systems. It elevates engineering to its rightful role as the driver of packaging line performance and enables lines to run as cohesive, predictable systems rather than collections of individual machines.

These differences become clear when the two models are compared side by side.

Equipment decisions drive the project. The system is built around the capabilities of individual machines, often tied to a single OEM platform.

Engineering leads the project. Requirements come first, equipment is selected to meet them, and comprehensive service ensures the system performs as designed.

- OEM-limited equipment selection

- System design constrained by fixed platform

- Machines optimized individually rather than for system interaction

- Strong equipment, weak system coordination

- OEM-neutral equipment selection

- Best-fit technologies from any supplier

- Machine centers chosen for their role in system behavior

- Engineering defines requirements; equipment fulfills them

- Interactions engineered late or inconsistently

- Controls logic varies across OEMs

- Higher risk of starved or backed-up machine centers

- Performance issues surface at production speeds

- System behavior engineered as a cohesive whole

- Controls, accumulation, and recovery defined around actual equipment

- Stable flow at constraint rates

- Predictable performance across shifts

- Machine scopes delivered independently

- No unified owner for coordinated system behavior

- Interaction issues often emerge at FAT/SAT or startup

- Support limited to machine performance rather than line performance

- One engineering-led partner

- Integrated execution from design through startup

- Clear ownership of system performance

- Support tied to throughput, uptime, and lifecycle needs

- Higher operational risk

- Slower ramp-up

- Performance limited by uncoordinated system behavior

- Greater cost variability when multiple OEMs are engaged independently

- Reduced risk

- Faster stabilization

- Stronger uptime, throughput, and predictable OEE

- Greater cost predictability through systems-first engineering and scope freeze discipline

How IPM Executes the Hybrid Integration Model

IPM delivers the Hybrid Integration Model by engineering the system around the client’s operational requirements and specifying machine centers and supporting systems to fulfill those outcomes. Every decision begins with what the line must achieve, not with the boundaries of any one equipment platform.

IPM’s execution model combines technical depth with disciplined service delivery. Engineering and controls define system behavior. Installation, commissioning, training, and ongoing support ensure that the behavior is achieved in production. This blend of technology and service enables IPM to deliver a system that performs as designed from startup through sustained operation.

In the Hybrid Integration Model, IPM serves as the client advocate, ensuring the system’s needs drive every equipment decision and the final solution is tailored to the client’s operation. IPM evaluates each machine center for its role in system behavior, its interactions with upstream and downstream equipment, and its contributions to long-term performance. Equipment is selected and specified based on what the engineered system requires, not on how it aligns with a single platform. This protects engineering flexibility and ensures the configuration reflects the client’s specific products, workflows, staffing model, and performance goals.

IPM applies this discipline through system-level engineering. Line architecture, rate behavior, accumulation strategy, controls logic, ergonomics, and operability are guided by one integrated engineering team working toward a unified performance objective. By resolving interactions and dependencies before equipment is placed, this approach avoids the mismatches that surface when machine choices precede system design.

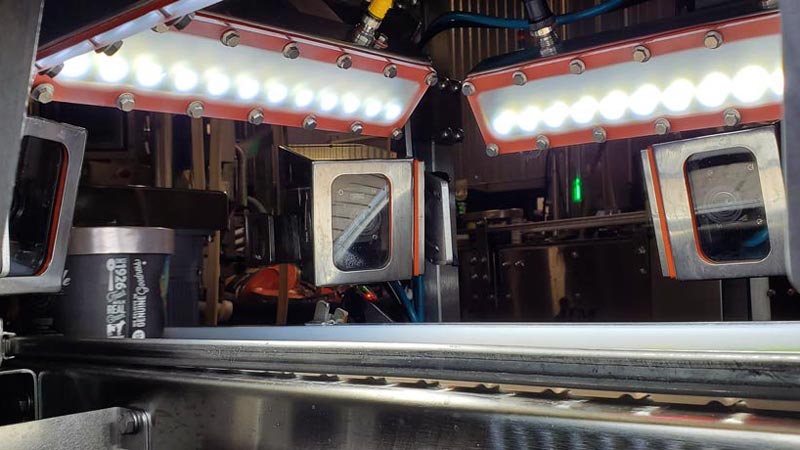

Execution turns engineering intent into operational performance. Controls logic, system modeling, and integration design flow directly into comprehensive service delivery, including installation and startup, FAT, SAT, training, and ongoing support. This end-to-end continuity, defined in the IPM Method, ensures the system is installed, validated, and supported with the same discipline that shaped its engineered design.

With systems-first engineering, OEM-neutral selection, and lifecycle ownership, IPM delivers packaging systems that reduce operational risk, stabilize flow, accelerate ramp-up, and strengthen the return on capital investment. The result is a system engineered for predictable performance, efficient flow, and long-term operational strength.

What sets Hybrid Integration apart is the combination of system technology and lifecycle service. Technology defines the engineered system. Service ensures it performs. This combination is difficult to replicate and is the core reason IPM can deliver packaging lines that run with stability, efficiency, and confidence.

A Systems-First Path to Maximizing Uptime, Efficiency, and ROI

Packaging lines face rising pressure to run faster, support broader SKU mixes, and operate with leaner teams amid growing automation and ongoing labor challenges. These demands expose a simple truth: performance is determined by the system’s behavior, not the strength of individual machines.

Hybrid Integration addresses this by aligning engineering, equipment selection, controls, and execution around one objective: predictable system performance. The result is a more stable operation for engineering teams and stronger capital efficiency for leadership.

As production demands increase, a systems-first model becomes essential to maximizing uptime, efficiency, and ROI across the lifecycle of the line.

Strengthen Performance.

Reduce Risk. Improve Returns.

Hybrid Integration equips your packaging line with engineered technology and disciplined service, creating the system-level coherence needed to protect uptime, efficiency, and capital strategy.